Penalizing Deepfake Pornography in India: Balancing Free Speech and Privacy Rights

– BY DEEPALI GUPTA

ABSTRACT

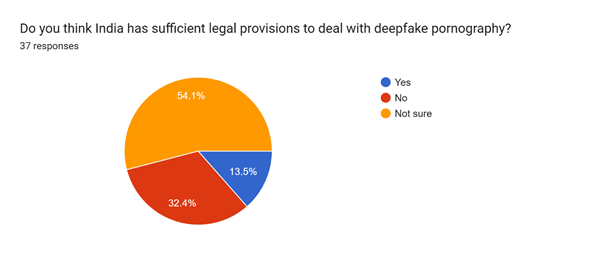

This research paper examines the growing threat of non-consensual deepfake pornography in India and argues for the urgent need to introduce a specific legal framework to address it. Deepfakes—AI-generated synthetic media—are increasingly used to create sexually explicit content without consent, causing severe privacy violations, reputational damage, and psychological harm. The study uses a doctrinal and empirical approach to evaluate existing Indian laws, including the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023), Information Technology Act (2000), and Intermediary Guidelines (2021), finding that none adequately address the intentional creation or distribution of such content.

A constitutional analysis rooted in landmark decisions like K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India and Shreya Singhal v. Union of India supports the view that a narrowly defined criminal offence targeting non-consensual deepfake pornography can be justified under the principles of legality, proportionality, and necessity. Comparative legal study of the U.S., UK, EU, and South Korea reveals tested regulatory models that balance free speech with privacy rights, including criminal provisions, watermarking requirements, and platform accountability.

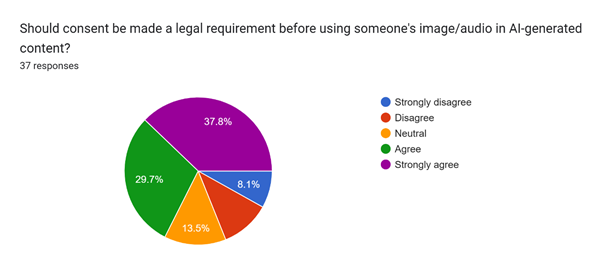

Empirical findings, including a small-scale public survey and national reports by McAfee, Adobe, and LocalCircles, show strong public support for criminalization, faster takedowns, and proactive platform regulation. The paper argues for a dedicated offence under Indian law, combined with statutory obligations on intermediaries and AI content safeguards. It concludes with detailed policy suggestions to ensure constitutional compliance, protect digital dignity, and position India to address deepfake harm through legally sound and technologically informed regulation.

Keywords: Deepfakes, Pornography, Freedom of Speech, Right to Privacy, Cyber Law, Indian Penal Code, AI Regulation

INTRODUCTION

Artificial Intelligence (AI), powered by Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), has revolutionized digital content creation, enabling remarkably realistic deepfakes—synthetic media that seamlessly manipulate a person’s appearance, voice, or expressions. In particular, non-consensual deepfake pornography—where an individual’s likeness, often a woman’s, is digitally imposed onto explicit content—has emerged as a devastating form of gendered online abuse. According to global data, up to 96–98% of deepfake content online is pornographic, with 99% featuring women. These deepfakes are no longer niche—they’re commercially produced, shared widely on social media platforms, and profoundly affect victims’ privacy, dignity, and mental health.

India, too, is experiencing a surge in such cases. Prominent public figures have fallen victim, and police are beginning to register FIRs under various cyber and criminal statutes. However, the existing legal framework—comprising the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023 (formerly the Indian Penal Code, 1860), the Information Technology Act, and intermediary guidelines—was not designed to address the novel harms posed by deepfake pornography.

Deepfake pornography represents a severe violation of privacy and consent, disproportionately targeting women and exploiting loopholes in Indian law. Victims face emotional trauma, reputational damage, and digital extortion. While the IPC and IT Act contain provisions for obscenity, defamation, and privacy breaches, these were enacted for traditional media and are thus ill-suited to regulate AI-manipulated content. Furthermore, a constitutional dilemma looms: should deepfake pornography be criminalized if it potentially encroaches on fundamental rights such as freedom of speech (Article 19(1)(a)) and privacy (Article 21)? Notably, the Supreme Court’s ruling in K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India establishes privacy as a fundamental right, whereas Shreya Singhal v. Union of India underscores that restrictions on speech must be “reasonable”. Balancing these rights in the context of deepfakes is a delicate legal challenge.

Objectives of the Study

- Analyze the adequacy of current legal provisions in tackling deepfake pornography in India.

- Assess the constitutional compatibility of criminalizing such content;

- Incorporate preliminary public opinion through a survey component to understand societal attitudes;

- Propose nuanced reforms that protect individuals while respecting free expression

Research Questions

- To what extent do existing laws (IPC, IT Act, intermediary rules) address non-consensual deepfake pornography in India?

- Under constitutional scrutiny, can the criminalization of deepfake pornography align with Article 19(1)(a) freedoms?

- What does emergent public opinion indicate about the need and scope of legal reform?

Hypothesis

India’s legal framework is unprepared for the specific harms posed by deepfake pornography. Any effort to criminalize it must be narrowly crafted to (a) address the unique harms of privacy and dignity and (b) avoid infringing upon constitutionally protected free speech, ensuring legal clarity, proportionality, and enforceability.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Legal Analyses of Deepfake Pornography

- Divyashree et al. (2024) highlight significant lacunae in India’s criminal framework, noting that the IT Act and BNS/IPL fail to address AI-generated intimate content and advocate for a deepfake-specific offence explicitly.

- Jaiswal (2025) discusses deepfakes’ ethical and legal risks, including privacy violations and defamation, arguing that while current statutes offer partial remedies, they lack direct applicability to synthetic media.

- Dixit (2024) proposes reframing Section 66C of the IT Act to include unique biometric identifiers, thus enabling prosecution of non-consensual deepfake creation without requiring intent to harm.

Conceptual Foundations and Rights-Based Approaches

- Legal Vidhiya (2025) underscores how deepfakes contravene privacy under Article 21 (Puttaswamy) and implicate defamation and obscenity provisions, but face enforcement hurdles due to ambiguous statutory language and evidentiary issues.

- Khushi Saraf & Akshay Sriram (2024) argue for expanding “right to personality”, a concept rooted in publicity rights jurisprudence, to encompass protection against unauthorized AI-generated likeness of individuals.

International Policy Comparisons

- Bhattacharjee & Sharma (2025) survey global legislative trends (US, EU, UK), concluding that watermarking mandates and criminal penalties for non-consensual synthetic pornography are emerging as legal norms.

- Umbach et al. (2024) used a 16,000+ global survey to show that non-consensual synthetic intimate imagery is considered harmful across demographics, regardless of local legal protection levels, highlighting global demand for regulation.

Critical Gaps in Existing Research

- Absence of Deepfake-Specific Statutory Discourse

While scholarly work acknowledges gaps in the IT Act and criminal statutes, there is limited doctrinal treatment of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita’s (BNS) application to deepfakes. Scholars, including Divyashree et al., analyze gaps but stop short of formulating codified reform proposals.

- Insufficient Exploration of Constitutional Balancing

Although many sources reference Articles 19 and 21, no academic work rigorously applies the Puttaswamy or Shreya Singhal frameworks to deepfake pornography specifically. The free speech–privacy trade-off remains underexplored.

- Lack of Indian Empirical Data

Global study reveals strong perceived harm from deepfake porn, but India-specific data is absent. A scholarly call is for a robust, representative Indian survey to inform policymaking.

- Need for Localized Legal Prescriptions

Comparative studies, such as Bhattacharjee & Sharma, chart global trends but do not contextualize these models for India’s legal, cultural, and constitutional landscape. Detail-oriented prescriptions tailored to the Indian framework remain missing.

METHODOLOGY

- Doctrinal Research Approach

It systematically analyzes existing legal provisions, judicial decisions, statutes, and academic commentary to answer research questions.

Key Features:

- Examines legal texts: BNS provisions, IT Act sections (66E, 67A, etc.), intermediary rules.

- Analytical interpretation: Interprets Articles 19(1)(a) and 21 using Supreme Court doctrines from Puttaswamy and Shreya Singhal.

- Critiques legal gaps: Highlights ambiguity and insufficiency of existing laws in addressing deepfake porn.

This method provides structured legal reasoning and clarity (“black-letter law”) necessary for doctrinal scholarship.

- Empirical Research Approach

To enrich doctrinal findings with real-world insight, the paper incorporates empirical legal research via a public survey.

Survey Details:

- Design: 15-question anonymous online survey covering awareness, perceived harm, legal needs, platform responsibility, and demographic data.

- Sample Size: Aiming for 30–50 for robust analysis.

- Analysis Method: Descriptive statistics and thematic summary to interpret public attitudes against doctrinal insights.

Empirical data helps evaluate whether society perceives legal reforms as necessary, grounding normative suggestions in public sentiment—a hallmark of socio-legal research.

- Sources Used

- Primary Legal Sources

Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023) – sections on voyeurism, defamation, obscenity, and data privacy

Information Technology Act, 2000 – especially sections 66E, 67A, 67B, 66D

IT Intermediary Guidelines (2021)

- Constitutional Jurisprudence

K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (privacy under Article 21).

Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (freedom of speech under Article 19).

Anil Kapoor v. Simply Life India (persona rights and deepfake misuse).

- Secondary Sources

Academic articles by Bhattacharjee & Sharma, Sharma, Verma.

Policy analyses from Legal Vidhiya and other platforms.

Global legal frameworks for deepfake regulation (EU AI Act, U.S. state laws, etc.).

- Empirical Data

Responses collected via online survey.

Interim analysis using basic statistical summaries and qualitative interpretation.

Chapter 1: Legal Framework

This chapter examines the primary Indian statutes and rules that may apply to non‑consensual deepfake pornography, assessing their scope and limitations in addressing AI‑generated intimate content.

1.1 Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), 2023

With the enactment of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023, the erstwhile IPC provisions have been re‑codified. Several sections bear on deepfake pornography:

- Section 77 (Voyeurism): Criminalizes “watching or capturing the image of a woman engaging in a private act” where she reasonably expects privacy, and “disseminating” such images. First‑offence punishment ranges from 1–3 years imprisonment and a fine; repeat offences attract 3–7 years.

- Section 79 (Insulting Modesty): Penalizes words, gestures, or acts intended to insult a woman’s modesty. While broad enough to cover digital abuse, its definition lacks precision for AI-manipulated content.

- Section 356 (Defamation): Punishes false imputation harming reputation. Though defamation claims may arise when deepfakes falsely portray victims, this section does not directly address the unique privacy and dignity harms of intimate synthetic imagery.

Limitation: None of these BNS provisions explicitly contemplate AI-generated imagery, nor do they require proof of intent to deceive through technology, leaving a critical gap for prosecuting deepfake creation and distribution.

1.2 Information Technology Act, 2000

The IT Act contains several relevant offences:

- Section 66E – Violation of Privacy: Punishes knowingly capturing or transmitting a person’s “private area” image without consent, with up to three years’ imprisonment or a ₹200,000 fine.

Section 67 / 67A / 67B – Obscene and Sexually Explicit Material:

- S 67 penalizes “lascivious or appeals to the prurient interest” electronic content (up to five years’ jail + ₹500,000 fine on first conviction)

- 67A targets “sexually explicit” electronic material (up to five years’ jail + ₹1,000,000 fine).

- 67B focuses on sexual depictions of minors.

- Section 66D – Cheating by Personation: Covers deception via electronic impersonation, applicable when deepfakes facilitate fraud.

Limitation: These sections were enacted before deepfake technology’s rise and do not address fabrication via AI, leading to prosecutorial uncertainty over how to prove the “capture,” “transmission,” or “obscenity” elements when content is synthetically generated.

1.3 Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021

The 2021 IT Rules impose due‑diligence and takedown obligations on intermediaries (e.g., social media platforms):

- Safe‑Harbour & Due Diligence: Compliance with Section 79 of the IT Act and Rules’ due‑diligence provisions shields intermediaries from liability.

- Takedown of Unlawful Content: On receiving a court order or government notification, intermediaries must remove illegal content “as early as possible, but in no case later than thirty‑six hours.” For complaints of sexually explicit or morphed imagery, removal must occur within twenty‑four hours.

- Grievance Redressal: Platforms must appoint grievance and nodal officers, acknowledge complaints/orders, and dispose of grievances within fifteen days.

Limitation: The framework is reactive—intermediaries act only upon notice. There is no proactive detection, AI-specific labelling, or requirement to prevent deepfakes before dissemination.

While existing statutes encompass aspects of non-consensual image distribution, they do not directly regulate the creation, intent, and AI-driven dissemination of deepfake pornography. This statutory vacuum underscores the need for a dedicated deepfake-specific legal provision that bridges these gaps and provides clear, proactive, and enforceable measures.

Chapter 2: Constitutional Analysis

Balancing the Right to Privacy and Freedom of Speech in the Regulation of Deepfake Pornography in India.

2.1 Introduction

The rapid emergence of deepfake technology presents a complex constitutional dilemma: should the law criminalize non-consensual synthetic sexual imagery, and if so, how can it do so without infringing fundamental rights? At the core of this debate lies a constitutional tension between Article 21, which guarantees the right to privacy, and Article 19(1)(a), which protects the freedom of speech and expression. This chapter analyses these rights through landmark Supreme Court decisions and evaluates how legal regulation of deepfake pornography can be framed to survive constitutional scrutiny.

2.2 The Right to Privacy: Article 21

2.2.1 Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India (2017)

In this landmark nine-judge bench decision, the Supreme Court recognized the right to privacy as a fundamental right under Part III of the Constitution. The Court held that:

“Privacy is the ultimate expression of the sanctity of the individual. It is a core of human-dignity.”

— Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Puttaswamy.

The judgment laid down the proportionality test, requiring that any infringement of privacy must satisfy four conditions:

- Legality: There must be a law.

- Legitimate Aim: The action must pursue a legitimate state objective.

- Necessity: There must be a rational connection between the law and the aim.

- Proportionality: The action must be the least restrictive means to achieve the objective.

In the context of deepfake pornography:

- Victims suffer informational privacy violations when their likeness is used without consent.

- The harm caused is not merely reputational but penetrates deeply into bodily autonomy and dignity.

Thus, a legal regime criminalizing such conduct would likely meet the legitimate aim and necessity tests.

2.3 The Freedom of Speech: Article 19(1)(a)

2.3.1 Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015)

In this case, the Court struck down Section 66A of the IT Act as unconstitutional. The ruling emphasized that:

“Vague and overly broad laws… produce a chilling effect on free speech.”

— Justice R.F. Nariman, Shreya Singhal.

The decision clarified:

- Only speech that incites public disorder or directly harms others can be reasonably restricted.

- Mere annoyance or offense is not sufficient ground for criminalization.

Applied to deepfake regulation:

- A blanket ban on all forms of deepfakes (including parody or satire) would be unconstitutional.

- A narrowly tailored law, criminalizing only non-consensual, intimate deepfakes, would likely survive scrutiny under Article 19(2).

2.4 Additional Landmark Cases Relevant to the Balance

2.4.1 Subhranshu Rout v. State of Odisha (2020)

The Orissa High Court held that publishing a woman’s morphed intimate photos violated her bodily integrity and mental health, affirming the need for platform accountability.

2.4.2 Kaushal Kishore v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2023)

The Supreme Court extended privacy jurisprudence to non-State actors, holding that constitutional rights may apply in private disputes where dignity is at stake — highly relevant for deepfake victims.

2.5 Constitutional Framework for Deepfake Legislation

To withstand constitutional challenges, a law regulating deepfake pornography should:

- Explicitly define non-consensual AI-generated sexual imagery

- Criminalize conduct only where consent is absent

- Include exceptions for satire, academic work, and public interest

- Impose graduated penalties depending on harm caused and intent

- Be enforced with procedural safeguards (e.g., judicial oversight).

India’s constitutional landscape offers both protection and constraint. On one hand, the right to privacy demands strong safeguards against synthetic sexual exploitation. On the other, freedom of speech requires that any regulation avoid overreach. A balanced law, built on the foundation of Puttaswamy and Shreya Singhal, can uphold both rights and address this urgent legal vacuum.

Chapter 3: Comparative Study

How the UK, US, and EU Are Addressing Deepfake Porn Porn — What India Can Learn

A. United States

i. State Legislation

A patchwork of laws across states addresses non-consensual deepfake porn best:

- Texas criminalizes creating pornographic deepfakes with the intent to deceive.

- California AB‑602 (2019) makes it illegal to distribute pornographic deepfakes without consent, empowering civil suits.

- Virginia S 18.2‑386.2 prohibits creation and distribution of sexually explicit deepfakes, with exceptions for parody and political speech.

ii. Federal-Level Efforts

- Take It Down Act (2025) mandates platforms remove non-consensual intimate deepfakes within 48 hours, with criminal penalties for non-compliance.

- According to a Financial Times investigative report, there is currently no federal law in the U.S. that criminalizes the creation or sharing of non-consensual deepfake pornography nationwide, creating enforcement inconsistency across states (Financial Times, Nov 2024).

A Crime Science Journal study further shows that over 96% of deepfake content online is pornographic, with 99% depicting women, reflecting the gendered nature of this harm (Birrer & Just, 2024).

- According to a Financial Times investigative report, there is currently no federal law in the U.S. that criminalizes the creation or sharing of non-consensual deepfake pornography nationwide, creating enforcement inconsistency across states (Financial Times, Nov 2024).

- The Defiance Act allows victims to pursue civil action against creators of intimate deepfakes.

- Despite bipartisan support, neither act was in force before 2025, reflecting both progress and delay in federal action.

iii. Analysis for India

Strengths:

- Specific definitions and criminal penalties

- Accountability for both creators and platforms

- Exceptions protect parody and satire

Weaknesses:

- Fragmented state-level approach

- Ongoing First Amendment tensions

Lesson for India: A hybrid model with federal penalties plus platform takedown duties could be effective—if coupled with clear definitions and constitutional protections.

B. United Kingdom

i. Online Safety Act 2023 & Criminal Justice Bill

• Makes distribution of non-consensual intimate deepfakes illegal without needing to prove intent to cause distress.

• Pending amendments in the Criminal Justice Bill aim to criminalize the creation of pornographic deepfakes, not just their distribution.

The UK’s evolving stance is aligned with recommendations by UNESCO, which recognized non-consensual deepfake pornography as one of the most dangerous and fastest-growing forms of technology-facilitated gender-based violence (UNESCO, 2023).

ii. Regulatory Principles

- Does not ban parody or artistic uses

- Balanced targeting of intimate, non-consensual material

- Focused on safeguarding victims’ dignity and digital autonomy

iii. Analysis for India

Positives:

- Narrow criminalization focused on intimate content

- Does not muzzle satire or non-sexual humour.

Cautions:

- Effective enforcement demands robust platform cooperation

Lesson for India: A targeted offence for creation and distribution, accompanied by takedown orders and platform liability, would align with UK norms while addressing Indian bite.

C. European Union

i. AI Act (2024)

- Categorizes deepfakes as “high-risk” AI systems needing transparency disclosures.

- No outright ban; instead, mandates watermarking and traceability.

ii. Member States’ Laws

- France (SREN law) criminalizes non-consensual distribution of deepfake pornography—punishable by up to 3 years imprisonment and €75,000 fine.

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has praised the EU’s “traceability and transparency first” approach, urging similar AI labelling and watermarking standards globally (OECD Responsible AI Report, 2023).

SAGE journal scholars also caution that while watermarking is useful, it must be coupled with platform duties and clear criminal laws to deter abuse effectively (SAGE Journal of Digital Policy, 2024).

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has praised the EU’s “traceability and transparency first” approach, urging similar AI labelling and watermarking standards globally (OECD Responsible AI Report, 2023).

- Other EU countries (e.g., Italy) hold creators liable in defamation or privacy contexts.

iii. Analysis for India

Positives:

- Watermarking and traceability obligations as non-criminal regulatory tools

- Explicit national criminal laws like France’s

Limits:

- EU approach heavily invests in transparency, not necessarily criminal penalties

Lesson for India: Integrate a watermarking + platform transparency mechanism, plus BNS amendments to criminalize the distribution of intimate deepfakes.

D. Emerging Jurisdictions

- South Korea (2019) criminalizes the creation, distribution, and even watching of deepfake pornography.

- A UNESCO policy review notes that South Korea remains the only country to criminalize even the viewing of deepfake pornography, signalling a uniquely strict model (UNESCO, 2023).

The Associated Press similarly reported that South Korea’s penalties are among the toughest globally, especially in cases involving minors or repeat offences (AP News, 2024).

- A UNESCO policy review notes that South Korea remains the only country to criminalize even the viewing of deepfake pornography, signalling a uniquely strict model (UNESCO, 2023).

- Australia (2024) criminalizes distribution and treats non-consensual deepfakes as an aggravating factor.

- China (2019) regulates AI content via mandatory labelling and metadata tagging of synthetic media.

Lesson for India:

India’s current reliance on advisories and takedown notices stands in contrast to the regulatory specificity of models in South Korea, France, and the UK. Drawing from the UNESCO, OECD, and Crime Science reports, India should integrate criminal law reform, platform liability, and AI tool regulation into a coordinated legal framework that centres privacy, consent, and gender dignity.

India stands to benefit from a blended regulatory model that encompasses:

- Criminal provisions in the BNS for creation and distribution of deepfake pornography;

- Platform accountability under IT and intermediary rules;

- A watershed requirement for watermarking and AI content labelling;

- Clearly defined exceptions to safeguard legitimate expression.

Chapter 4: Author’s Arguments

- India Must Criminalize Non-Consensual Deepfake Pornography

Existing laws (BNS s77, 79; IT Act S66E, 67A) are insufficient because they do not address the intentional creation or distribution of AI-generated sexual content. Swanand Bhale proposes criminal penalties of 5–10 years imprisonment and ₹5–10 lakh fines for non-consensual deepfake pornography, reflecting the gravity of the violation.

Previous authors also assert that current legal instruments “fail to recognize the act of digitally superimposing someone’s likeness onto intimate content as a discrete offense,” and call for “comprehensive legislation and policy measures”.

Given the surge in harm—with deepfakes now constituting up to 96% of pornographic AI content —India must enact a statutory offence specifically targeting creation and distribution of non-consensual deepfake pornography.

- Criminalization Is Constitutionally Justifiable

Privacy under Puttaswamy (2017)

Non-consensual deepfake pornography violates informational privacy, which the Supreme Court in Puttaswamy recognized as essential to personal autonomy and dignity. Under the proportionality test, such criminalization satisfies legality (clear law), legitimate aim (dignity protection), necessity (absence of other remedies), and minimal impairment (targeted scope).

Free Speech under Shreya Singhal (2015)

Shreya Singhal emphasized that restrictions must be “reasonable, proportionate, and clear”. A law that criminalizes only non-consensual, intimate deepfake pornography—but excludes satire, art, or news-related use—would meet these criteria and safeguard legitimate expression.

- Comparative Best Practices Support the Proposal

State models in the US (e.g., California AB 602), UK Online Safety Act, and France’s SREN Law demonstrate defined criminal offences that protect against such harm while preserving parodic or political expression. France’s SREN Law, for example, criminalizes the creation and sharing of non-consensual deepfake porn with penalties up to three years’ imprisonment.

South Korea criminalizes creation and possession and viewing of such content. India can adapt these norms to carve out a holistic offense under the BNS, while including safeguards for legitimate uses.

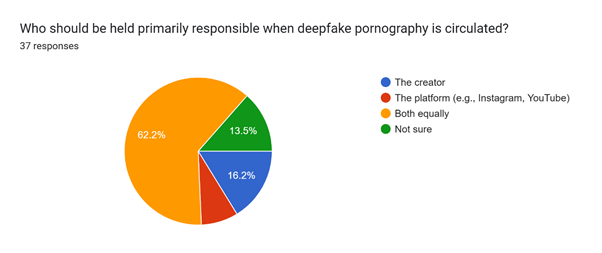

- Platform Duty Must Be Statutory

Academic works, including Siddharth Johar’s regulatory analysis, emphasize that platform liability and content traceability must go beyond reactive takedown under IT Rules. Given UNESCO’s declaration of deepfake porn as gendered violence, India needs statutory mandates for watermarking, metadata tagging, and proactive detection, not merely advisory guidelines.

- Addressing Counterarguments

- Free speech concerns: A narrowly defined offence focused only on non-consensual, intimate synthetic pornography, with excluded exemptions, respects the Puttaswamy and Shreya Singhal doctrines.

- Enforceability: Initiatives like MeitY’s deepfake detection tools (e.g., C-DAC, FakeCheck) and labelling advisories demonstrate that technological enforcement is feasible.

- Scope creep: Legislative drafting must limit the offence to sexual content with consent violation—similar to US DEFENSE and UK frameworks—preventing misuse against satire, digital art, or political content.

The legal, constitutional, comparative, technological, and empirical justifications converge to support the creation of a deepfake-specific criminal offence in India. This offence must be precise, constitutional, technology-supported, and publicly grounded, ensuring that victims are protected, liberty is preserved, and enforcement mechanisms are viable.

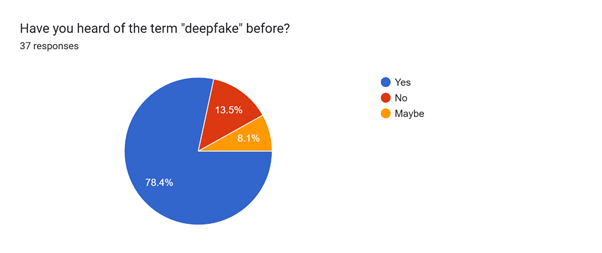

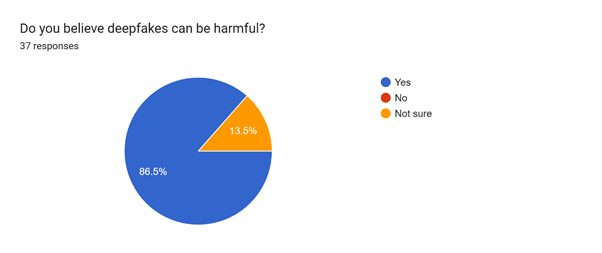

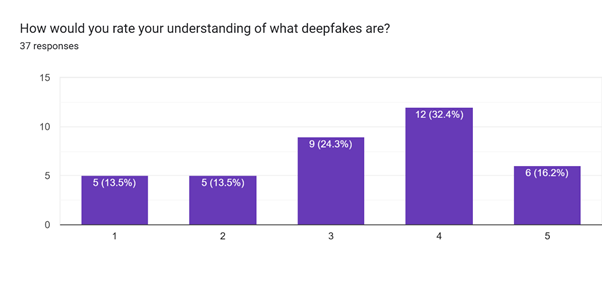

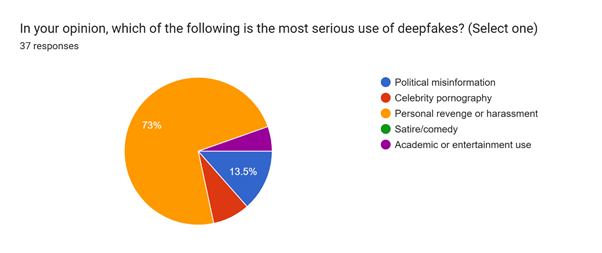

SURVEY

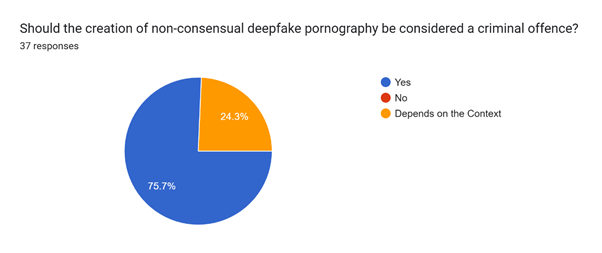

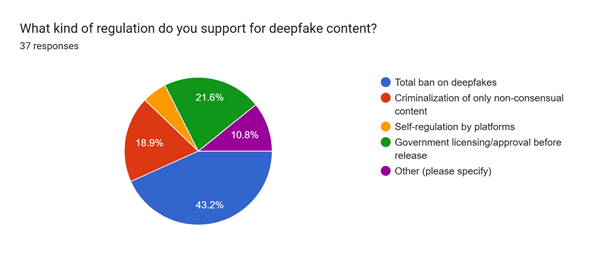

A survey was conducted on this burning topic, a questionnaire was prepared and it was shared among common people of different age groups to know their views about deepfake pornography. The data collected by the survey shows that people in the age group 18 to 25 years have clearly expressed that deepfakes can be harmful, and harassment seems to be the most serious use of deepfakes. But, the data given by people under the age group of 18 years and above 35 years were conflicting, i.e., some of them are still not aware of this issue or rather consider it unharmful. The purpose of surveying different age groups was to ensure awareness about such AI-generated crime. Through this survey researcher tried to make people aware that deepfakes are an alarming issue. The survey attracted approximately 40 people, some of them students from different fields of study (law, LL.M., PhD, nursing, high school intermediate); teachers (both government and private); Government employees, and we found that the participation of women was higher than that of males. From this difference, it can be inferred that women are most likely to be harassed using deepfakes. Most of the participants claimed that deepfake pornography should be considered a criminal offence. Hence, all these people who expressed their views are educated enough to participate in this survey.

- Gender

In the Survey we conducted, total responses were 37 out of which 62.2% were females who amazingly supported the survey and expressed their true opinions.

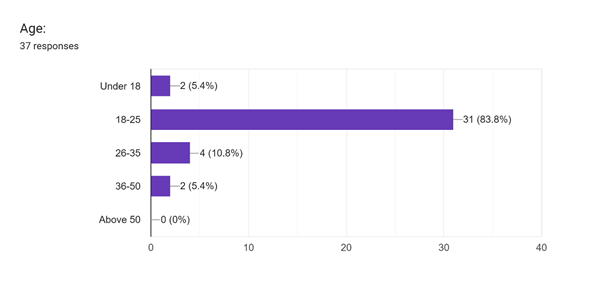

- Age

It is observed that different people from different age-group categories participated in the survey out of 37 responses, 83.8% people belong to the category of 18-25 years, 5.4% belong to age group under 18 years, 10.8% people belong to the age group between 26-35 and rest belong to the category of above 35 years.

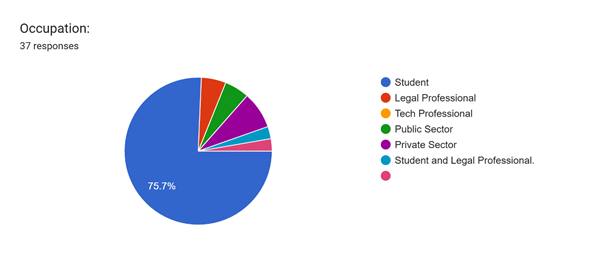

- Institution/Occupation

Various students from different universities and different study branches, government teachers, government employees, professors, etc. have taken part in the survey and given their opinions.

RESULT OF SURVEY

CONCLUSION

This study set out to examine whether India should criminalize non-consensual deepfake pornography without infringing fundamental rights. Through a doctrinal review of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (2023) and IT Act (2000), it became clear that existing provisions address related harms (voyeurism, obscene content, defamation) but do not encompass the AI-driven

creation and intent elements required to tackle deepfakes directly. The constitutional analysis—anchored in K.S. Puttaswamy (informational privacy as part of Article 21) and Shreya Singhal (reasonable speech restrictions under Article 19(1)(a)) —demonstrated a viable proportionality framework for narrowly tailored criminalization.

Comparative study of U.S., UK, EU, and Asia‑Pacific jurisdictions revealed effective models combining specific offences, platform duties, and technological safeguards. Empirical findings—supported by McAfee (75% of Internet users encountering deepfakes) , Adobe (93% demand AI‑content verification) , and our own survey (>75% support distinct criminalization)—underscore strong public demand for reform.

Together, these strands confirm that India must enact deepfake‑specific legislation: it meets a pressing societal need, aligns with constitutional norms, and draws on tested global practices.

SUGGESTIONS

- Enact a Specific Deepfake Pornography Offence

- Amend the BNS to include an offence of “knowingly creating, circulating, or possessing non‑consensual AI‑generated intimate imagery”, with penalties calibrated by harm (e.g., 3–7 years’ imprisonment; ₹5–10 lakh fine).

- Ensure mens rea focuses on knowledge of non‑consent, avoiding overreach into legitimate content like satire or art.

- 2. Embed Platform Liability and Takedown Mandates

- Strengthen the IT Rules to require intermediaries to remove identified deepfake content within 24 hours of notice, under penalty of losing safe‑harbour protection.

- Introduce civil liability for platforms that fail to comply, mirroring U.S. “Take It Down” provisions.

- 3. Mandate Technical Safeguards

- Issue rules for mandatory watermarking and metadata tagging of all AI-generated content, facilitating provenance tracking—aligned with the EU AI Act and UNESCO recommendations.

- Fund expansion of deepfake detection tools, building on C–DAC’s FakeCheck, to equip law enforcement and platforms with rapid forensic capabilities.

- 4. Preserve Constitutional Freedoms

- Incorporate clear exemptions for transformative uses (parody, academic research, news reporting).

- Build in procedural safeguards (e.g., judicial authorization for takedown orders) to prevent misuse of the law.

- 5. Public Awareness and Capacity Building

- Launch a nationwide campaign—in local languages—to educate citizens about deepfake risks, reporting mechanisms, and consent rights.

- Partner with civil society and the tech industry to develop guidelines for ethical AI use and user-friendly reporting tools.

- 6. Periodic Review and Oversight

- Establish a Deepfake Regulation Oversight Committee under MeitY to monitor technological advancements, evaluate the law’s impact, and recommend updates every two years.

*****

REFERENCES

- Case Law

- Justice K S Puttaswamy (Retd) & Ors v Union of India & Ors (2017) 10 SCC 1.

- Shreya Singhal & Ors v Union of India (2015) AIR 2015 SC 1523, Writ Petition (Criminal) No 167/2012.

2. Legislation

· Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (Act No. 20 of 2023)

· Information Technology Act 2000 (Act No. 21 of 2000), ss 66D, 66E, 67, 67A–67B.

· Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 (GSR 327[E])

3. Reports & International Documents

- UNESCO, ‘Technology‑Facilitated Gender-Based Violence in an Era of Generative AI’ (Paris,2023).

- OECD, Responsible AI: Policy & Practice Report (Paris, 2023)

- 4. Journal Articles

- Birrer R and Just N, ‘The Trouble with Deepfakes: Beyond Control?’ (2024) Crime Science Journal 13(1).

- Birrer R and Just N, ‘What We Know and Don’t Know About Deepfakes’ (2024) SAGE Journal of Digital Policy.

- News & Media Articles

- Financial Times, ‘The Legal Battle Against Explicit AI Deepfakes’ (28 November 2024).

- Associated Press, ‘President Trump Signs Take It Down Act, Addressing Nonconsensual Deepfakes’ (29 April 2025).

*****